Evidence Based

Evidence Based

Evidence Based

This article is objectively based on relevant scientific literature, written by experienced medical writers, and fact-checked by a team of degreed medical experts.

Our team of registered dietitian nutritionists and licensed medical professionals seek to remain objective and unbiased while preserving the integrity of any scientific debate.

The articles contain evidence-based references from approved scientific sites. The numbers* in parentheses (*1,2,3) will take you to clickable links to our reputable sources.

Osteoporosis Statistics & Facts 2024 – Things You May Not Know

Osteoporosis is quite a common bone disease that creeps in slowly and is frequently only diagnosed after bone breakage or fracture. Because of this, it has been named a silent disease because it weakens the bones with no symptoms manifesting. The most dreadful complication of this condition is a bone fracture.

Osteoporosis isn’t gender discriminative; however, studies support that it is pretty prevalent in postmenopausal women over 50. Its prevalence in 2017-2018 in the U.S. within this age group[1] was 12.6%, with a higher prevalence among women (19.1%) than men (4.4%). The lower the socioeconomic status,[2] the lower the awareness of the disorder.

Worldwide, osteoporosis affects about 200 million women.[3] By 2050, hip fractures will have increased by 310% in men and 240% in women.[3]

Disease-associated life years, or DALYs, are an indicator of population health. Generally speaking, the global burden of DALYs increased from 1990 to 2019, doubling from 8.6 million[1] in 1990 to 16.6 million in 2019. Diet, exercise, and lifestyle choices are huge factors. This osteoporosis statistics piece will detail osteoporosis projections, the factors, and how you can reduce your risks.

Key Osteoporosis Facts

- Osteoporosis is a bone weakening disease increasing the risk of fractures and breakages.

- One in ten[4] Americans over fifty has osteoporosis.

- In their lifetime, one in two women and one in four men[5] break a bone due to osteoporosis.

- Diet and supplements, exercise, medication, and lifestyle modifications may aid in treating and managing osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis Statistics In The United States

Osteoporosis statistics in the United States over the years have been a growing concern. With numbers lingering in the millions, researchers have done their due diligence to trace the causes that heighten the risks of osteoporosis.

According to one CDC[6] data brief, the prevalence of osteoporosis is based on the following:

- Age: There is a 12.6%[6] prevalence rate in people over 50 for femoral neck and lumbar spine osteoporosis between 2017 and 2018.

- Sex: Men over 50 had a 4.4%,[1] and women had a 19.6% prevalence between 2017-2018.

- Low bone density: In men 65 and older, osteoporosis prevalence is at 40.7%[6] and 27.5%[6] in men aged 50–64.

These are the factors that contribute to the prevalence of osteoporosis:

- Ethnicity and Race: In the United States, white women[7] have the highest fracture rates, and black women’s rates are about 50% lower. Asian women and Hispanic women have a general 25% rate lower than white women.

- Nutrition: An inadequate intake of bone health minerals[8] like calcium, vitamin D, potassium, or magnesium can contribute to the development of osteoporosis. Deficiency in protein, vitamins K and C, omega-three fatty acids, folate, and vitamin B-12 may also lead to a deterioration in bone health.

- Lifestyle factors: Sedentary lifestyles, including physical inactivity, high soft drink intake, and lack of weight-bearing exercise,[9] may reduce bone density.

- Genetic factors: Low bone mineral density heritability is 60% to 80%[10] in families with twins.

- Hormonal factors: The rate of osteoporosis[11] in women aged 45–49 doubles every half a decade at the rate of 3.3%. This number progressively increases to 50.3% at age 85 due to bone loss and hormonal imbalances that cause estrogen deficiency.

- Smoking and alcohol consumption: People who smoke and drink alcohol are at a higher risk of developing osteoporosis[12] compared to those who do not.

- Medical conditions: People with rheumatoid arthritis have a 27.6%[13] prevalence of osteoporosis. People with gastrointestinal disorders[14] are also at significant risk, mainly due to the malabsorption of nutrients needed for bone health.

- Healthcare access to low-income level groups: People in low-income groups with limited access to internal medicine and healthcare services and awareness face diagnosis and treatment delays.

How Has The Prevalence Of Osteoporosis Changed Over Time?

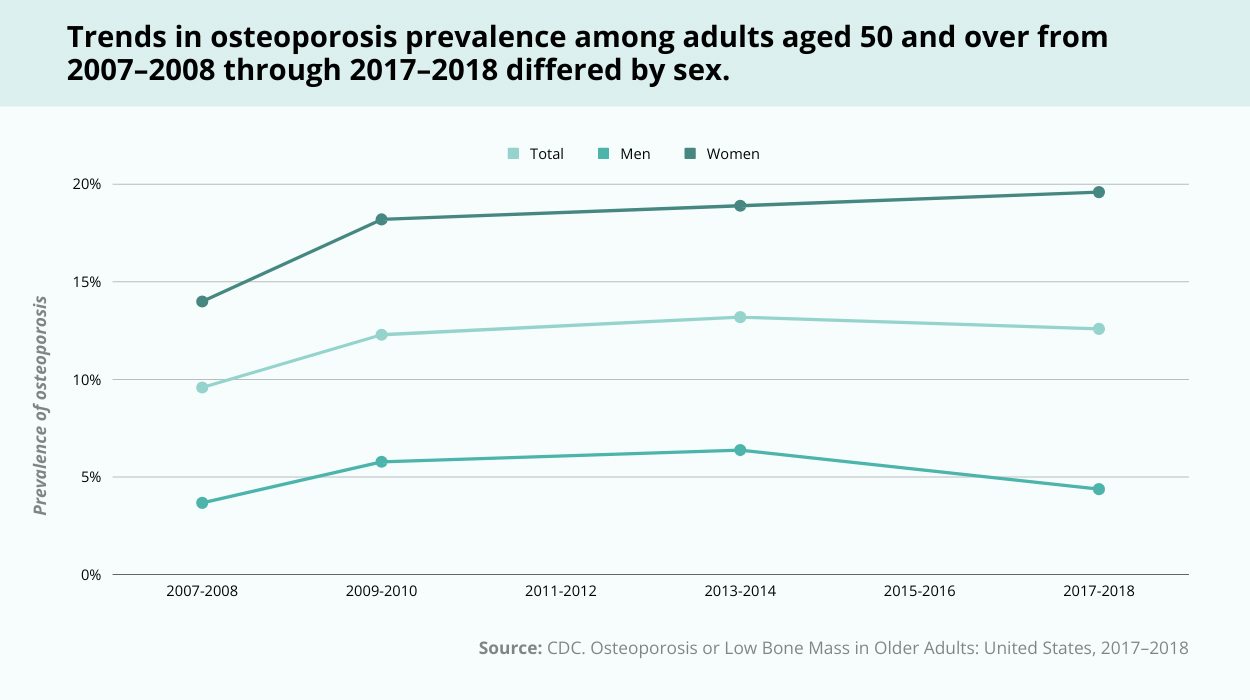

From this survey,[15] there is a clear indication that women’s prevalence of osteoporosis is on an upward trajectory compared to men.

For instance:

- Between 2007-2008 and 2009-2010, women’s prevalence grew from about 14% to 18%.[6] Men’s was from 3.7% to 5.8%.[1]

- Between 2009-2010 and 2013-2014, women’s prevalence grew slowly from 18.2% to 18.9%. Men’s was from 5.8% to 6.4%.[1]

- Between 2013-2014 to 2017-2018, women’s prevalence grew from about 18.9% to 19.6%.[6] Men’s prevalence dropped from 6.4% to around 4.4%.[6]

Men’s prevalence of osteoporosis is generally lower, driven by slow growth, and then dropped significantly in 2018.

In Older Adults

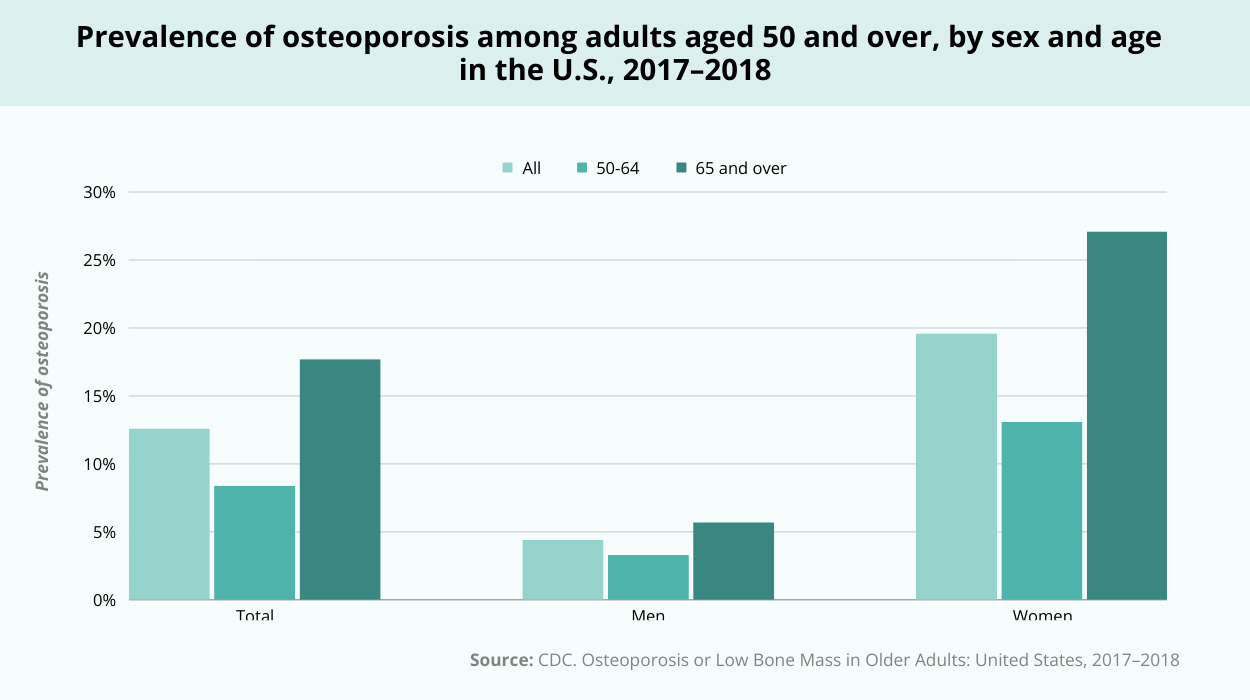

Osteoporosis

- Age-adjusted rates of osteoporosis at the lumbar spine, femur neck, or both were 12.6%[15] in adults 50 years of age and older and 17.7%[15] in people 65 years of age and older, compared to 8.4%[15] in adults 50–64.

- Women followed a similar pattern, with 27.1%[15] of those over 65 and 13.1%[15] of those between 50 and 64. It was not statistically significant that there was an age difference among men 5.7%[15] for those 65 and older versus 3.3%[15] for those 50–64. Women were more likely than males to have osteoporosis among all people in both age groups.

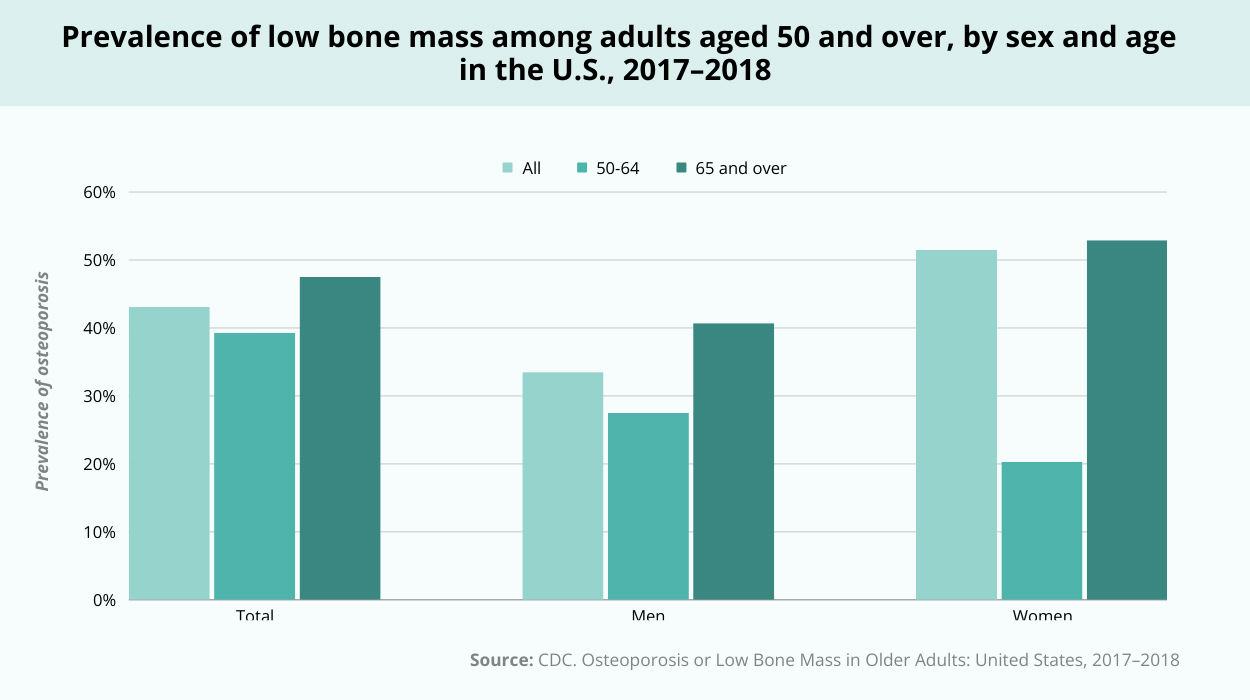

Low Bone Mass

- When comparing individuals 50 years of age and older to those 65 years of age and older, the age-adjusted prevalence of low bone mass at the femur neck, lumbar spine, or both was 43.1%.[15] It was 39.3%[15] among persons 50–64 years of age and 47.5%[15] among adults 65 and above.

- Compared to men aged 50–64, 27.5%,[15] men 65 and older 40.7%[15] had a higher prevalence of low bone mass. Women aged 50–64 50.3%[15] and 65 and older 52.9%[15] did not significantly differ in the prevalence of poor bone mass. The frequency of low bone mass was greater in women than in men across all persons and all age groups.

Other Facts To Know

- 34 million[16] more Americans are at risk of developing osteoporosis than the 10 million[16] Americans over 50 who currently have the condition.

- Osteoporosis-related fractures mostly occur in different skeletal sites like the hip, spine, and wrist. Spinal fractures occur without noticeable symptoms, possibly leading to height loss and a hunched posture.

- The Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, i.e., DEXA scan,[17] is the most common and precise osteoporosis scan. Doctors use it to measure bone density and diagnose osteoporosis.

- Three types of bone loss occur before and after the development of osteoporosis. Osteopenia is the moderate bone loss that occurs before osteoporosis develops with a lower fracture risk. A higher fracture risk severely characterizes osteoporosis. Osteomalacia[18] is an issue related to adequate mineralization of the bone.

- Although osteoporosis is prevalent in older adults, it may occur at any age. It may affect younger people due to chronic disease and medications that affect bone health. Other factors are autoimmune diseases, endocrine dysfunction, malabsorptive disease, and psychiatric disease.[19]

- Osteoporosis impacts your emotional and social well-being. Psychological stress and depression[20] are some common effects of dealing with this disorder.

When Does Osteoporosis Occur?

It is key to note that there are two main types: primary and secondary.

Simply put, primary osteoporosis occurs naturally without any underlying medical conditions. Primary osteoporosis is divided into two: postmenopausal and senile. Postmenopausal osteoporosis occurs in older women aged 40 and above, and senile osteoporosis occurs in men and women due to age.

Secondary osteoporosis is when there is an underlying medical condition that compromises your normal bone mass health. Here, factors like chronic diseases, gastrointestinal disorders, hormonal disorders, and rheumatologic disorders may contribute.

Most studies support that this bone mineral loss is mostly prevalent in postmenopausal women. Bone loss happens in two stages.[21] The first is the starting phase of menopause, which sees a decline in estrogen levels. The second stage is four to eight years later.[21]

If you can access medical diagnosis early, you can manage the development of the disease. With early diagnosis, you can carry out primary and secondary prevention measures. Primary being medical interventions such as Prolia injections or bisphosphonates, secondary being supplementation, such as with calcium and vitamin D while living healthy.

Steven Fiore,[22] MD, a Board-Certified Orthopedic Surgeon and the founder of Cannabis MD Telemed,[22] explains the importance of early diagnosis.

“Early diagnosis of osteoporosis in adults and children with bone-related ailments offers several benefits. It allows for timely intervention to slow down bone loss and reduce the risk of fractures. Early treatment can also help manage underlying causes and prevent complications, contributing to better overall bone health. In children, early detection is crucial for addressing developmental issues and promoting optimal bone growth.”

Steven Fiore, MD.

Vitamin D deficiency alone was found to account for 55.3% of osteoporosis cases[23] in Columbia.

Why Is Osteoporosis More Common In Females?

Females are more likely to develop osteoporosis due to their biology.

Biologically, women have lower bone densities, lower vitamin D levels, and higher bone remodeling markers. A lower bone density means that the bone has lower mineral content. So, as a woman ages and bone density naturally decreases, the bones grow porous and weaker faster than men.

Lower vitamin D levels[24] affect calcium absorption from foods. This affected absorption heightens a woman’s risk of developing osteoporosis,[25] and supplementation with calcium[26] is deemed ineffective. Lastly, having higher remodeling markers leads to[27] faster bone reabsorption.

Another biological factor is the hormonal changes that occur during menopause. This results in a rapid decline in estrogen levels. Estrogen aids in the health maintenance of bone growth and turnover.[28]

A deficiency seen during menopause accelerates bone mass loss, making women more susceptible to osteoporosis.

Jabe Brown,[29] the founder of Melbourne Functional Medicine,[30] attests women are prone to osteoporosis due to hormonal changes.

“Healthcare professionals need to develop gender-specific interventions, especially since women are more prone to osteoporosis due to hormonal changes post-menopause. Tailored lifestyle and dietary recommendations, along with hormone replacement therapies where appropriate, can be effective.”

Jabe Brown, BHSc (Nat), MSc (Nut & Fx-Med), BComm, AFMCP, the Founder of Melbourne Functional Medicine

What Is The Difference Of Osteoporosis In Men And Women?

Osteoporosis in men and women is quite similar, but there are some key differences:

- Prevalence: Men’s osteoporosis prevalence is mostly linked to older age. For the total population of adults over 50, men’s prevalence of osteoporosis is a quarter that of women.[31]

- Hormonal factors: In women, the decline in estrogen during menopause is a significant factor contributing to osteoporosis. The gradual reduction in testosterone[32] levels with age is a contributing factor in men.

- Age of onset: For men, osteoporosis typically occurs later in life compared to women. Women often experience fastened bone loss after menopause, while men usually see a gradual decline in bone density in their 50s and 60s. This may be because men have[33] bigger bones and reach a higher peak bone mass.

- Fracture patterns: Osteoporosis-related fractures in women typically occur in the hip, spine, and wrist. In men, subsequent vertebral fractures are uncommon but are twice as frequent.[34]

- Underdiagnosis in men: Osteoporosis in men is sometimes underdiagnosed and undertreated. This is because it is often perceived as a women’s health issue; despite these differences, diagnosis, prevention, and management basics remain standard.

How To Prevent Osteoporosis

One may take different approaches based on the contributing factors to prevent osteoporosis-related fractures.

According to Jabe Brown,[29] the Founder of Melbourne Functional Medicine, recognizing subtle signs early aids in early prevention.

“Subtle signs, including a reduction in grip strength, receding gums, or a decrease in height, can indicate early bone density loss. Educating individuals to recognize these signs can lead to earlier interventions.”

Jabe Brown, BHSc (Nat), MSc (Nut & Fx-Med), BComm, AFMCP, the Founder of Melbourne Functional Medicine.

Here are some possible remedies based on risk factors to practice early on:

Diet Modifications To Mitigate Nutrient Deficiencies

You need nutrients that facilitate healthy bone. These should build your bone mineral content, its mass, geometry, and microstructure. The nutrients[35] that aid bone health are:

- Calcium: Incorporate cheese, yogurt, beans, lentils, almonds, and leafy greens into your diet.

- Vitamin D: Add foods like cod liver oil, sardines, tuna fish, salmon, cereals, and natural juices fortified with vitamin D to your meals. Have your blood levels checked and supplement as needed.

- Vitamin K: Eat plenty of green leafy veggies, soya beans, and canola oil.

- Polyphenols: Eat plenty of foods rich in polyphenols, such as berries, herbs, spices, nuts, flax seeds, and olives.

The following expert remark emphasizes that diet is an important part of preventing osteoporosis.

“Holistic approaches in primary care for comprehensive bone health promotion involve integrating nutritional counseling, exercise recommendations, and lifestyle modifications. Primary care providers can emphasize the importance of a balanced diet, adequate vitamin D, and regular physical activity tailored to individual needs.”

Steven Fiore, MD (Board-Certified Orthopedic Surgeon).

Besides foods, you may also look into herbs and dietary supplements offering bone-strengthening properties. Some examples of herbal remedies[36] for osteoporosis fractures are:

- Cannabis sativa[36] speeds up the healing process.

- Piper sarmentosum[36] enhances fracture healing.

- Cissus quadrangularis[36] boosts bone healing.

Supplements that may also offer prevention and treatment remedies are calcium, vitamin D, K, and polyphenol-rich supplements.

Bone-Strengthening Exercises

Weight-bearing exercises, like walking, jogging, and resistance training, stimulate bone formation and help prevent osteoporosis.

A bone and mineral research[37] highlighted the following exercises to help prevent osteoporosis:

- Walking alone may not improve significant bone mineral mass. But a consistent program with 30 minutes daily may.

- Aerobic training with high speed and intensity may reduce bone mineral mass loss. Examples of these exercises are jogging and stepping.

- Bone strength training improves bone density in the neck of the femur and the lumbar spine. Three sessions per week are recommended.

- Resistance training in your lower limbs is the most effective at improving bone mineral mass in the neck of the femur.

Avoid Bone Health-Compromising Habits

Smoking tobacco affects your bone mineral mass and influences the bone turnover rate.[38] This leads to a higher loss in bone mass, heightening the risk of one or more fractures due to osteoporosis.

Consuming alcohol from three standard drinks per day increases the occurrence of osteoporotic fractures.[39] And the higher the consumption rate, the higher the risk.

Smoking cessation and limiting alcohol intake, therefore, become essential lifestyle changes to preserve your bone density.

Hormone-Replacement Therapy For Pre And Postmenopausal Women

Hormone-replacement therapy can be helpful medical guidance to help reduce the impact of low estrogen levels. This may lessen the effects of hormonal fluctuations on bone health.

This estrogen-replacement therapy helps decrease all osteoporosis-related fractures.[40]

Regular Bone Density Screenings

Screening for osteoporosis is recommended in postmenopausal women and men aged 50 and older with risk factors. Experts achieve it using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) testing of the hip and spine.

Jabe Brown,[29] the founder of Melbourne Functional Medicine, offered the following remedies, including regular screenings:

“To combat the silent nature of osteoporosis, awareness campaigns targeting the at-risk demographic (women over 50 and men to a lesser extent) are essential. These should focus on educating about regular bone density screenings, the importance of a balanced diet rich in calcium and vitamin D, and the role of weight-bearing exercises in maintaining bone health.”

Jabe Brown, BHSc (Nat), MSc (Nut & Fx-Med), BComm, AFMCP.

Stay Educated On Emerging Studies On Osteoporosis

Staying aware of the new data related to the condition helps you prevent it better. Awareness campaigns empower you with the knowledge to make informed choices for your bone health.

Steven Fiore, MD (Board-Certified Orthopedic Surgeon), the founder of Cannabis MD Telemed, highlights research as essential.

“Specific interventions for osteoporosis should consider gender differences in risk factors. For men, targeted educational programs and research on effective treatments are essential. Currently, available therapies, including bisphosphonates and monoclonal antibodies, have shown efficacy in reducing fracture risk. Ensuring accessibility to these treatments involves addressing affordability and improving healthcare infrastructure.”

Steven Fiore, MD (Board-Certified Orthopedic Surgeon), the founder of Cannabis MD Telemed

The Takeaways

Osteoporosis, affecting millions, has a profound impact on life. So, understanding its causes, prevention, and maintaining bone health is paramount.

Bone loss as we age is inevitable. However, you may reduce the rate at which it deteriorates. You may incorporate a healthy, balanced diet, exercise more, try hormonal replacement therapy, and attend regular screenings. Educating yourself and staying aware of emerging studies also goes a long way.

See a doctor before trying any of the above-mentioned prevention tips and treatments.

The global prevalence of osteoporosis is common among older people, but it may also affect the younger generations. So, ensure regular screenings for an all-rounded approach to prevent future fractures and treat the condition.

Frequently Asked Questions

Osteoporosis is common in women over 50, including 60-year-old women. Of the 200 million women with osteoporosis, one-third are older women[41] who experience osteoporotic fractures.

Osteoporosis progression varies based on the contributing factor. Bone loss typically occurs gradually. Factors like age, genetics, and lifestyle contribute. Regular bone density osteoporosis screening helps monitor progression and inform preventive methods.

The fastest way to increase bone density involves a combination of weight-bearing exercises and a balanced diet rich in calcium and vitamin D. Also, avoid harmful habits like smoking and excessive alcohol consumption.

Milk is a good drink for bone density, providing calcium and vitamin D essential for bone health. Other bone-healthy beverages include fortified plant-based milk, orange juice, and mineral waters.

Hormones, particularly estrogen, are crucial in maintaining bone density. In postmenopausal women, the decline in estrogen levels contributes to accelerated bone loss, increasing the risk of osteoporosis.

While osteoporosis cannot be completely reversed, osteoporosis treatment and lifestyle changes can slow its progression and reduce fracture risk.

Yes, men can develop osteoporosis, especially in later years. Advanced age, low testosterone levels, and lifestyle factors contribute to the risk.

Osteoporosis can impact daily life by increasing the risk of bone fractures, leading to pain, disability, and a reduced quality of life.

+ 41 sources

Health Canal avoids using tertiary references. We have strict sourcing guidelines and rely on peer-reviewed studies, academic researches from medical associations and institutions. To ensure the accuracy of articles in Health Canal, you can read more about the editorial process here

- Anon, (2023). Products – Data Briefs – Number 405 – March 2021. [online] Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db405.htm

- Min Hyeok Choi, Ji Hee Yang, Jae Seung Seo, Kim, I. and Kang, S.-W. (2021). Prevalence and diagnosis experience of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women over 50: Focusing on socioeconomic factors. PLOS ONE, [online] 16(3), pp.e0248020–e0248020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248020.

- Shen, Y., Huang, X., Wu, J., Lin, X., Zhou, X., Zhu, Z., Pan, X., Xu, J., Qiao, J., Zhang, T., Ye, L., Jiang, H., Ren, Y. and Shan, P.-F. (2022). The Global Burden of Osteoporosis, Low Bone Mass, and Its Related Fracture in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2019. Frontiers in Endocrinology, [online] 13. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.882241.

- Health.gov. (2014). Osteoporosis – Healthy People 2030 | health.gov. [online] Available at: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/osteoporosis

- Osteoporosis Fast Facts. (n.d.). Available at: https://www.bonehealthandosteoporosis.org/wp-content/uploads/Osteoporosis-Fast-Facts-2.pdf.

- Anon, (2023). Products – Data Briefs – Number 405 – March 2021. [online] Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db405.htm#:~:text=Overall%2C%20the%20age%2Dadjusted%20prevalence,19.6%25%20in%202017%E2%80%932018.

- Cauley, J.A. and Nelson, D.A. (2021). Race, ethnicity, and osteoporosis. Elsevier eBooks, [online] pp.453–475. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-813073-5.00019-8.

- Muñoz-Garach, A., García-Fontana, B. and Muñoz‐Torres, M. (2020). Nutrients and Dietary Patterns Related to Osteoporosis. Nutrients, [online] 12(7), pp.1986–1986. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12071986.

- Hammad, L. and Benajiba, N. (2017). Lifestyle factors influencing bone health in young adult women in Saudi Arabia. African Health Sciences, [online] 17(2), pp.524–524. doi:https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v17i2.28.

- Collet, C., Ostertag, A., Manon Ricquebourg, Delecourt, M., Giulia Tueur, Isidor, B., Guillot, P., Schaefer, E., Javier, R., Funck‐Brentano, T., Philippe Orcel, Jean‐Louis Laplanche and Cohen‐Solal, M. (2017). Primary Osteoporosis in Young Adults: Genetic Basis and Identification of Novel Variants in Causal Genes. JBMR plus, [online] 2(1), pp.12–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10020.

- Cheng, C.-H., Chen, L. and Chen, K.-H. (2022). Osteoporosis Due to Hormone Imbalance: An Overview of the Effects of Estrogen Deficiency and Glucocorticoid Overuse on Bone Turnover. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 23(3), pp.1376–1376. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031376.

- Yang, C.-Y., Jerry Cheng-Yen Lai, Huang, W., Hsu, C.-L. and Chen, S.-J. (2021). Effects of sex, tobacco smoking, and alcohol consumption osteoporosis development: Evidence from Taiwan biobank participants. Tobacco Induced Diseases, [online] 19(June), pp.1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/136419.

- Samaneh Moshayedi, Baharak Tasorian and Amir Almasi‐Hashiani (2022). The prevalence of osteoporosis in rheumatoid arthritis patient: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, [online] 12(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20016-x.

- Merlotti, D., Mingiano, C., Valenti, R., Guido Cavati, Calabrese, M., Pirrotta, F., Scheme Alberto Palazzuoli and Gennari, L. (2022). Bone Fragility in Gastrointestinal Disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 23(5), pp.2713–2713. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23052713.

- Sarafrazi, N., Wambogo, E. and Shepherd, J. (2017). Osteoporosis or Low Bone Mass in Older Adults: United States, 2017-2018 Key findings. [online] Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db405-H.pdf.

- Clynes, M., Harvey, N.C., Curtis, E.M., Fuggle, N.R., Dennison, E. and Cooper, C. (2020). The epidemiology of osteoporosis. British Medical Bulletin. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldaa005.

- Anwar, F., Hiba Iftekhar, Taher, T., Syeda Kanza Kazmi, Rehman, F.Z., Humayun, M. and Mahmood, S. (2019). Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry Scanning and Bone Health: The Pressing Need to Raise Awareness Amongst Pakistani Women. Cureus. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.5724.

- Luisella Cianferotti (2022). Osteomalacia Is Not a Single Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 23(23), pp.14896–14896. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314896.

- Herath, M., Cohen, A., Ebeling, P.R. and Milat, F. (2022). Dilemmas in the Management of Osteoporosis in Younger Adults. JBMR plus, [online] 6(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10594.

- Chen, K., Wang, T., Tong, X., Song, Y., Hong, J., Sun, Y., Zhuang, Y., Shen, H. and Yao, X.I. (2024). Osteoporosis is associated with depression among older adults: a nationwide population-based study in the USA from 2005 to 2020. Public Health, [online] 226, pp.27–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.10.022.

- Ji, M. and Yu, Q. (2015). Primary osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine, [online] 1(1), pp.9–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdtm.2015.02.006.

- Linkedin.com. (2023). cannabismd-telemed | LinkedIn. [online] Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/company/cannabismd-telemed/

- Erika-Paola Navarro Mendoza, Jorge-Wilmar Tejada Marín, Cristina, D., Guzmán, G. and Luis Guillermo Arango (2016). Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in patients with osteoporosis. Revista Colombiana de Reumatología (English Edition), [online] 23(1), pp.17–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcreue.2016.04.003.

- Ijmrhs.com. (2023). International Journal of Medical Research and Health Sciences. [online] Available at: https://www.ijmrhs.com/

- Fleet, J.C. (2022). Vitamin D-Mediated Regulation of Intestinal Calcium Absorption. Nutrients, [online] 14(16), pp.3351–3351. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14163351.

- Reid, I.R. (2014). Should We Prescribe Calcium Supplements For Osteoporosis Prevention? Journal of Bone Metabolism, [online] 21(1), pp.21–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.11005/jbm.2014.21.1.21.

- Gurban CV;Balaş MO;Vlad MM;Caraba AE;Jianu AM;Bernad ES;Borza C;Bănicioiu-Covei S;Motoc AGM (2019). Bone turnover markers in postmenopausal osteoporosis and their correlation with bone mineral density and menopause duration. Romanian journal of morphology and embryology = Revue roumaine de morphologie et embryologie, [online] 60(4). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32239087/

- Emmanuelle Noirrit‐Esclassan, Valera, M.-C., Trémollières, F., Arnal, J., Françoise Lenfant, Fontaine, C. and Vinel, A. (2021). Critical Role of Estrogens on Bone Homeostasis in Both Male and Female: From Physiology to Medical Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 22(4), pp.1568–1568. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22041568.

- Linkedin.com. (2023). Jabe Brown | LinkedIn. [online] Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jabebrown/

- Mfm.au. (2017). Melbourne Functional Medicine. [online] Available at: https://mfm.au/

- Khaled Alswat (2017). Gender Disparities in Osteoporosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, [online] 9(5), pp.382–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr2970w.

- Kazuyoshi Shigehara, Izumi, K., Yoshifumi Kadono and Mizokami, A. (2021). Testosterone and Bone Health in Men: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, [online] 10(3), pp.530–530. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10030530.

- Sigríður Björnsdóttir, Clarke, B.L., Mannstadt, M. and Bente Langdahl (2022). Male osteoporosis-what are the causes, diagnostic challenges, and management. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, [online] 36(3), pp.101766–101766. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2022.101766.

- Farr, J.N., L. Joseph Melton, Achenbach, S.J., Atkinson, E.J., Khosla, S. and Amin, S. (2017). Fracture Incidence and Characteristics in Young Adults Aged 18 to 49 Years: A Population-Based Study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, [online] 32(12), pp.2347–2354. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3228.

- Zhang, Q. (2023). New Insights into Nutrients for Bone Health and Disease. Nutrients, [online] 15(12), pp.2648–2648. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122648.

- Singh, V. (2017). Medicinal plants and bone healing. National journal of maxillofacial surgery, [online] 8(1), pp.4–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-5950.208972.

- Maria Grazia Benedetti, Giulia Furlini, A. Zati and Giulia Letizia Mauro (2018). The Effectiveness of Physical Exercise on Bone Density in Osteoporotic Patients. BioMed Research International, [online] 2018, pp.1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4840531.

- Al-Bashaireh, A.M., Haddad, L., Weaver, M.T., Xing, C., Debra Lynch Kelly and Yoon, S.L. (2018). The Effect of Tobacco Smoking on Bone Mass: An Overview of Pathophysiologic Mechanisms. Journal of Osteoporosis, [online] 2018, pp.1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1206235.

- Justyna Godos, Giampieri, F., Chisari, E., Micek, A., Paladino, N., Forbes‐Hernández, T.Y., Quiles, J.L., Battino, M., Sandro La Vignera, Musumeci, G. and Grosso, G. (2022). Alcohol Consumption, Bone Mineral Density, and Risk of Osteoporotic Fractures: A Dose–Response Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, [online] 19(3), pp.1515–1515. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031515.

- Gambacciani, M. and Levancini, M. (2014). Featured Editorial Hormone replacement therapy and the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Przeglad Menopauzalny, [online] 4, pp.213–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.5114/pm.2014.44996.

- Gui-fang, L., Liu, C., Liang, T., Zhang, Z., Qin, Z. and Zhan, X. (2023). Predictors of osteoporotic fracture in postmenopausal women: a meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, [online] 18(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-04051-6.