Expert's opinion

Expert's opinion

Expert's opinion

The article is a subjective view on this topic written by writers specializing in medical writing.

It may reflect on a personal journey surrounding struggles with an illness or medical condition, involve product comparisons, diet considerations, or other health-related opinions.

Although the view is entirely that of the writer, it is based on academic experiences and scientific research they have conducted; it is fact-checked by a team of degreed medical experts, and validated by sources attached to the article.

The numbers in parenthesis (1,2,3) will take you to clickable links to related scientific papers.

L Glutamine For Gut Health 2024: How Does It Heal Your Leaky Gut?

Leaky gut is a syndrome many people struggle with nowadays and with the cure still being unknown, it’s no wonder they’re still hoping for a miracle. Could L Glutamine supplementation be the answer to help heal their leaky gut and promote metabolism?

How Does L Glutamine Heal Your Leaky Gut?

Glutamine has an important role in our immune system and our gut health. It acts as an important energy source[1] for our immune cells as well as the cells of the intestinal wall which depend on it to survive and function properly.

This way, taking l glutamine supplements helps maintain the health of our intestinal wall barrier[2], protecting against leaky gut syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by increased intestinal permeability which allows bacteria and toxins to pass through and cause inflammation.

L Glutamine For Gut Health

Glutamine has an important role in our immune system and our gut health. It acts as an important energy source[1] for our immune cells as well as the cells of the intestinal wall which depend on it to survive and function properly.

This way, glutamine helps maintain the health of our intestinal wall barrier[2], protecting against leaky gut syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by increased intestinal permeability which allows bacteria and toxins to pass through and cause inflammation.

Specific growth factors and various nutrients act as mucosal protective factors which preserve the gut barrier integrity. A form of glutamine, L Glutamine, is the most abundant amino acid in the blood and it plays a vital role in the maintenance of mucosal integrity.

Featured Partner

Low-Calorie

Non-GMO

Vegan-friendly

Get Blown Away By Expert-Crafted Formula

Learn More About Colon Broom – one of the quality supplements promoting regular bowel movements, alleviates bloating, and supports healthy cholesterol levels.

Leaky Gut Syndrome

In its essence, the leaky gut syndrome[3] isn’t a syndrome per se, it’s a digestive condition that involves bacteria and toxins “leaking through” the intestinal wall. This can wreak havoc on the body and potentially cause a myriad of issues such as intestinal diseases, autoimmune diseases, migraines, chronic fatigue syndrome, hormonal imbalances, mood swings, and other issues.

Celiac disease[4], diabetes[5], irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)[6], and Crohn’s disease[7], as well as many food allergies and intolerances[8], have increased intestinal permeability at their core, as bacteria and toxins cause almost irreparable inflammation and damage.

Although the intestinal wall already has specific small gaps, its role is to let water and nutrients in, not bacteria. Once these gaps, also called tight junctions[9], become loose, they make the gut more permeable and allow bacteria, antigens, and toxins to pass through. This condition is then called increased intestinal permeability, also known as leaky gut.

Once the pathogens leak through the intestinal wall, they can enter the bloodstream and cause extensive damage and inflammation which can cause our immune system to activate and start fighting.

The most common symptoms[10] of leaky gut include:

- Bloating

- Digestive discomfort

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Fatigue

- Bad breath

- Food sensitivities

- Skin sensitivity and breakouts

The Cause Of Leaky Gut

Although the exact cause of the leaky gut is still unknown, the research did shine some light on certain factors that characterize it. A protein called zonulin[11] is the only regulator of intestinal permeability. When activated, it can lead to leaky gut syndrome. The most common reasons for its activation[12] are intestinal bacteria and gluten, the protein found in wheat, barley, and rye.

That being said, researchers agree on some specific factors which can play a major role in the development of leaky gut syndrome. These include:

- Nutrient deficiencies (specifically zinc[13], vitamin A, and vitamin D)

- Eating disorders and malnutrition

- Chronic inflammation[14]

- Chronic stress[15]

- Candida[16] overgrowth

- Unhealthy diet (processed foods and excessive sugar intake)

- Alcohol abuse[17]

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[18] (NSAIDs)

Glutamine

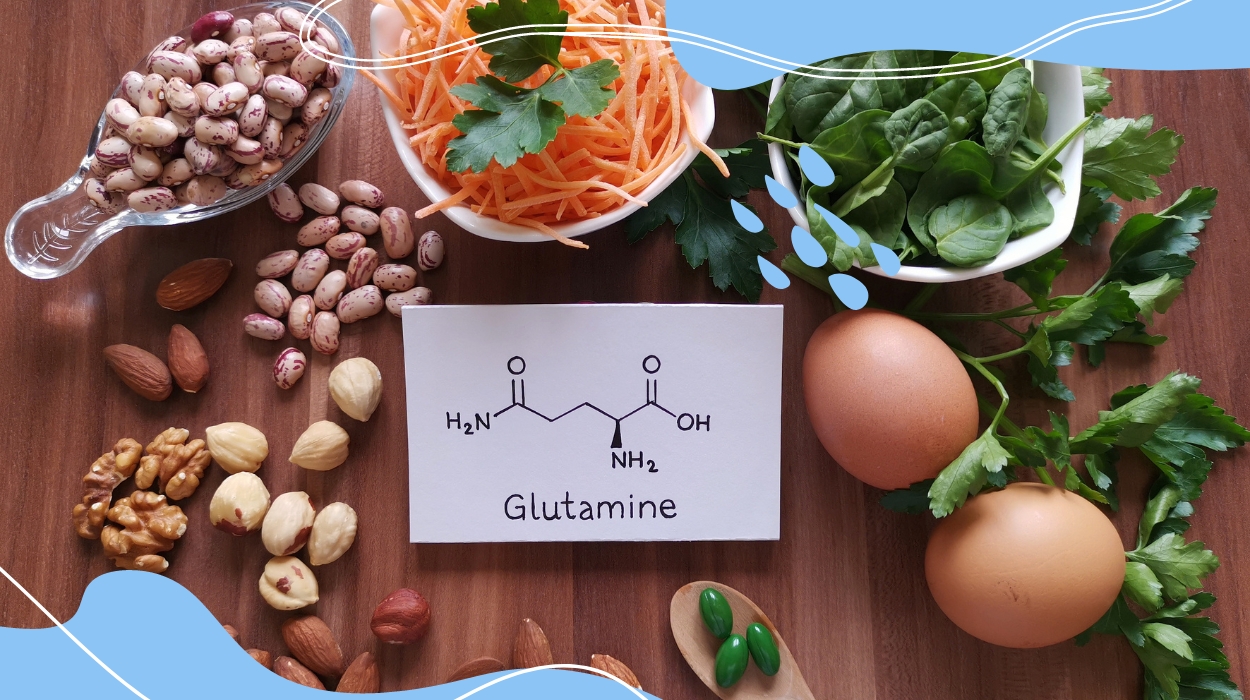

This amino acid is the most abundant and versatile[19] in the human body. It’s an essential nutrient and a building block of the immune system with a special role in intestinal health and promoting metabolism. It can be found in many foods, but it’s also produced by our bodies, which makes it hard to know whether we’re intaking enough.

Since it’s being produced and synthesized by our bodies, it should be considered a non-essential amino acid, one we don’t have to obtain from food. However, it’s considered a conditionally essential amino acid, which means that it has to be obtained from food under certain conditions, such as injury or illness.

Glutamine exists in two different forms: L-glutamine and D-glutamine[20]. L-glutamine is used to build proteins and perform other functions, but D-glutamine seems to have no specific important roles.

Glutamine can be found in many foods, with the largest amounts in animal products. Those that are most abundant include eggs, chicken, beef, fish, pork milk, tofu, lentils, and beans.

Glutamine And The Immune System

Glutamine’s most important role is in helping fuel the immune system. It’s an amazing energy source for white blood cells[21] as well as specific cells of the intestinal wall. Therefore, the health of the immune system can be compromised when glutamine levels are beyond ideal or imbalanced in some way.

Some illnesses, burns[22], surgeries, and wounds can cause glutamine levels to drop as the body then works hard to break down protein, so a high-protein diet will most likely be recommended as a part of the therapy treatment. Specific studies[23] even showed its incredible positive effect on healing and decreasing infections after some surgeries.

Furthermore, studies[24] found how you take dietary glutamine supplements can drastically improve a patient’s state when in critical conditions.

Gut Microbiome

Also called our “second brain[25], the gut microbiome[26] is a collection of all of the bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms residing in our gut. It’s incredibly important in the functioning of our entire organism, with a specific role in immune health[27] and brain health.

Every one of us has a different microbiome from the moment of birth and passing through the mother’s birth canal and breast milk. Later on, everything else we get in contact with shapes our microbiome and either makes it beneficial or places a greater risk for disease.

Environmental exposures, air pollution, diet, as well as stress all impact our microbiome and change the balance between good and bad bacteria. Everyone has a blend of beneficial and potentially harmful bacteria which work in unison to maintain a healthy environment for nutrients.

The microbiome works hard to synthesize macro and micronutrients, as well as to break down potentially toxic food compounds and help flush them out of our system. Furthermore, Some vitamins, like B12, can only be synthesized from enzymes found in bacteria. When that balance is compromised, it can create space for inflammation and diseases.

The gut-brain connection became an important field of research in recent years as their cross-communication is thought to be the key to a plethora of diseases and issues in the human body, hoping to be the miracle that will not only help heal but also prevent them from developing in the first place.

The network of neurons in our gut and brain communicate with each other all the time, but when faced with stress and inflammation, the fight-or-flight response is triggered, causing the digestion to stop so all of the energy can be diverted to the situation causing the threat. This just goes to show how strong the connection between these two areas actually is and how important it is to maintain a healthy microbiome.

Additional Ways To Heal Your Gut Health

It’s important to know you’re more than capable of helping your gut heal by implementing some healthy routines into your lifestyle. Such as:

- Reducing and limiting your intake of processed foods, sugars, alcohol, and cigarettes

- Lowering your stress levels by actively working on it through self-care – meditation, exercise, journaling, reading, walking in nature

- Taking probiotics and prebiotics[30] to improve your gut flora

- Improving your sleep routine

- Limit the use of NSAIDs

- Eating fermented foods such as sauerkraut, kefir, miso, and and kombucha to replenish your good bacteria

- Taking vitamin and mineral supplements

- Eating foods high in antioxidants such as berries and pomegranate to help fight free radicals and decrease or prevent oxidative damage

+ 30 sources

Health Canal avoids using tertiary references. We have strict sourcing guidelines and rely on peer-reviewed studies, academic researches from medical associations and institutions. To ensure the accuracy of articles in Health Canal, you can read more about the editorial process here

- Kim, H. (2011). Glutamine as an Immunonutrient. Yonsei Medical Journal, [online] 52(6), p.892. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22028151/.

- Wang, B., Wu, G., Zhou, Z., Dai, Z., Sun, Y., Ji, Y., Li, W., Wang, W., Liu, C., Han, F. and Wu, Z. (2014). Glutamine and intestinal barrier function. Amino Acids, [online] 47(10), pp.2143–2154. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24965526/.

- Mu, Q., Kirby, J., Reilly, C.M. and Luo, X.M. (2017). Leaky Gut As a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology, [online] 8. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5440529/.

- Sander, G.R., Cummins, A.G. and Powell, B.C. (2005). Rapid disruption of intestinal barrier function by gliadin involves altered expression of apical junctional proteins. FEBS Letters, [online] 579(21), pp.4851–4855. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16099460/ [Accessed 30 Sep. 2021].

- de Kort, S., Keszthelyi, D. and Masclee, A.A.M. (2011). Leaky gut and diabetes mellitus: what is the link? Obesity Reviews, [online] 12(6), pp.449–458. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21382153/.

- camilleri and gorman (2007). Intestinal permeability and irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, [online] 19(7), pp.545–552. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17593135/.

- HOLLANDER, D. (1986). Increased Intestinal Permeability in Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Their Relatives. Annals of Internal Medicine, [online] 105(6), p.883. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3777713/.

- Ventura, M.T., Polimeno, L., Amoruso, A.C., Gatti, F., Annoscia, E., Marinaro, M., Di Leo, E., Matino, M.G., Buquicchio, R., Bonini, S., Tursi, A. and Francavilla, A. (2006). Intestinal permeability in patients with adverse reactions to food. Digestive and Liver Disease, [online] 38(10), pp.732–736. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16880015/.

- Balda, M.S., Fallon, M.B., Van Itallie, C.M. and Anderson, J.M. (1992). Structure, regulation, and pathophysiology of tight junctions in the gastrointestinal tract. The Yale journal of biology and medicine, [online] 65(6), pp.725–35; discussion 737-40. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2589754/.

- Arrieta, M.C. (2006). Alterations in intestinal permeability. Gut, [online] 55(10), pp.1512–1520. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1856434/.

- Fasano, A. (2012). Intestinal Permeability and Its Regulation by Zonulin: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, [online] 10(10), pp.1096–1100. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3458511/.

- Fasano, A. (2011). Zonulin and Its Regulation of Intestinal Barrier Function: The Biological Door to Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Cancer. Physiological Reviews, [online] 91(1), pp.151–175. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21248165/.

- Skrovanek, S. (2014). Zinc and gastrointestinal disease. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology, [online] 5(4), p.496. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4231515/.

- Hietbrink, F., Besselink, M.G.H., Renooij, W., de Smet, M.B.M., Draisma, A., van der Hoeven, H. and Pickkers, P. (2009). SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATION INCREASES INTESTINAL PERMEABILITY DURING EXPERIMENTAL HUMAN ENDOTOXEMIA. Shock, [online] 32(4), pp.374–378. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19295480/.

- Konturek PC;Brzozowski T;Konturek SJ (2011). Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. Journal of physiology and pharmacology : an official journal of the Polish Physiological Society, [online] 62(6). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22314561/.

- Yamaguchi, N. (2006). Gastrointestinal Candida colonisation promotes sensitisation against food antigens by affecting the mucosal barrier in mice. Gut, [online] 55(7), pp.954–960. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1856330/.

- Ferrier, L., Bérard, F., Debrauwer, L., Chabo, C., Langella, P., Buéno, L. and Fioramonti, J. (2006). Impairment of the Intestinal Barrier by Ethanol Involves Enteric Microflora and Mast Cell Activation in Rodents. The American Journal of Pathology, [online] 168(4), pp.1148–1154. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16565490/.

- Bjarnason, I. and Takeuchi, K. (2009). Intestinal permeability in the pathogenesis of NSAID-induced enteropathy. Journal of Gastroenterology, [online] 44(S19), pp.23–29. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19148789/.

- Cruzat, V., Macedo Rogero, M., Noel Keane, K., Curi, R. and Newsholme, P. (2018). Glutamine: Metabolism and Immune Function, Supplementation and Clinical Translation. Nutrients, [online] 10(11), p.1564. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6266414/.

- Newsholme, P., Procopio, J., Lima, M.M.R., Pithon-Curi, T.C. and Curi, R. (2003). Glutamine and glutamate?their central role in cell metabolism and function. Cell Biochemistry and Function, [online] 21(1), pp.1–9. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12579515/.

- Demling, R.H. (2009). Nutrition, anabolism, and the wound healing process: an overview. Eplasty, [online] 9, p.e9. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2642618/ [Accessed 30 Sep. 2021].

- Lin, J.-J., Chung, X.-J., Yang, C.-Y. and Lau, H.-L. (2013). A meta-analysis of trials using the intention to treat principle for glutamine supplementation in critically ill patients with burn. Burns, [online] 39(4), pp.565–570. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23313017/.

- Fan, Y., Yu, J., Kang, W. and Zhang, Q. (2009). Effects of Glutamine Supplementation on Patients Undergoing Abdominal Surgery. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, [online] 24(1), pp.55–59. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19382426/.

- Griffiths RD;Jones C;Palmer TE (2017). Six-month outcome of critically ill patients given glutamine-supplemented parenteral nutrition. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), [online] 13(4). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9178278/.

- Ochoa-Repáraz, J. and Kasper, L.H. (2016). The Second Brain: Is the Gut Microbiota a Link Between Obesity and Central Nervous System Disorders? Current Obesity Reports, [online] 5(1), pp.51–64. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4798912/.

- Shreiner, A.B., Kao, J.Y. and Young, V.B. (2015). The gut microbiome in health and in disease. [online] 31(1), pp.69–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/mog.0000000000000139.

- Wu, H.-J. and Wu, E. (2012). The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes, [online] 3(1), pp.4–14. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3337124/.

- Pandey, Kavita.R., Naik, Suresh.R. and Vakil, Babu.V. (2015). Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics- a review. Journal of Food Science and Technology, [online] 52(12), pp.7577–7587. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4648921/.